Simulating Physics in a Computer: Another Matrix

Table of Contents

Emulation vs Simulation #

Before we deep dive into this topic, it is better to clarify the difference between emulation and simulation. They both appear to do the same thing but has a subtle difference to them which, in our case, makes for an enormous difference in perspective of what’s happening. Let us take an example to demonstrate the difference.

Going back in time(flashback it is) #

It is difficult to choose which console to buy. I love all the games which different console has to offer. Should I go with Nintendo DS, NES, SNES, Game Boy Advance, Saga, or other competitive products from different providers? Should I stick to PS1 or go for Xbox? It is a difficult choice to make, not to say of making an informed decision, as there is no internet connectivity like in the future where reviewers give you hints over which might suit us better.

Back to Track #

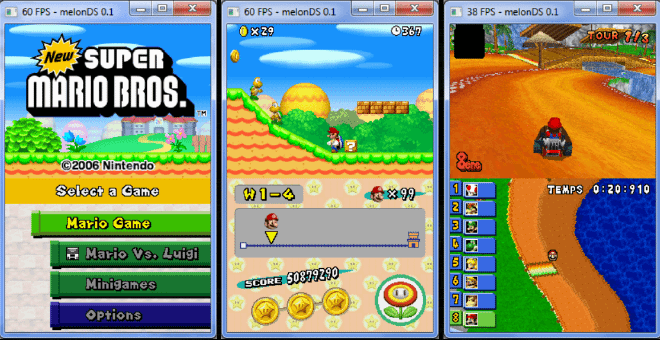

Modern computers have become powerful that it is possible to run the console games just like the games built for the specific PC and operating system. We have a lot of emulators(get it?) to make this possible. It has also enabled piracy to a great extent that we can play these console games for free if we know how to obtain a copy of them.

Here is the difference we have to focus on. Running the console games as is, i.e, the disk having the game files which is run on a modern PC is emulation. An attempt to recreate the game from scratch to make it run on the PC is simulation. This difference will ensure that a lot of pitfalls in our thoughts are eradicated, just as they appear to us.

In this article, we are talking about simulation, no emulation. We are trying to recreate the physics of our world to work on a computer. We, in no way, are talking about running the world around us on a computer(not a matrix, phew!).

Setting the Stage #

There are two different ways one can simulate physics inside a computer. On the obvious one, the other, more esoteric enough to give birth to a new technology called Quantum Computers.

The Obvious One #

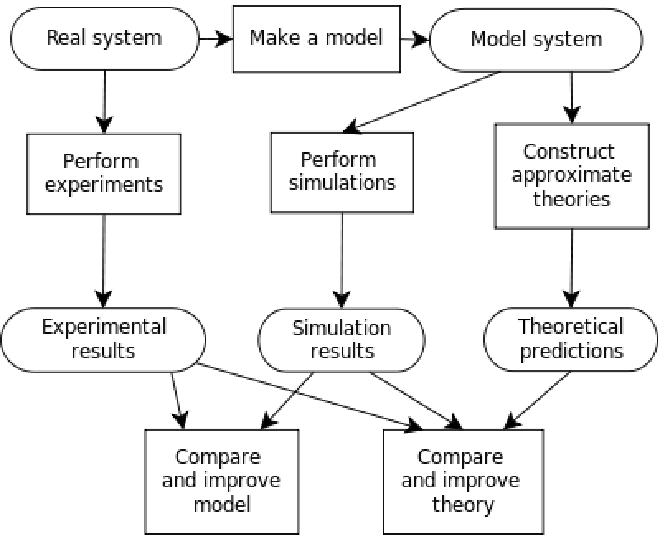

Physics is full of differential equations(sometimes multiple ones coupled to each other) and matrices. Their solutions help us understand the dynamics of the variables defining the evolution of the system which we are studying. Solving these complex equations is one way of simulating the physics in a computer. We have developed numerical algorithms to do the same and have been quite successful. However, nature demands more. The equations and systems we study become more complex that we need supercomputers to solve them in a realistic time.

One of my ideologies is that every theoretical physicist must be equipped with the right tools and techniques to simulate the system which he/she is studying. I believe that this is the first stop for a closer look at experimental verification, as it helps us look into things that we might overlook while solving equations by pen-and-paper.

Take, for example, Quantum Mechanics- it is in no way resembling classical physics or showing a realistic limit to classical equations of motion. At least on the first try. It takes time to get to Erhenfest’s theorem to see the parallel between the commutator and Poisson brackets which we loved to use in Classical Mechanics(Nah, not really loved to, but an elegant one). Let us also see a counterexample. We have both special and general relativity, which took the help of the Galilean frame transformations and Newtonian gravity respectively to complete the theory in the first place. The point is, in research, we never know which farmland we stumble upon, the one which makes no sense and is diametrically extinct or the one which makes sense only after relating it to the older ways. We need to be prepared to face both scenarios, and for that, I wish more people knew how to play around with supercomputers to get their physicsing up and running without these simple obstacles.

The Not So Common Approach of Simulation #

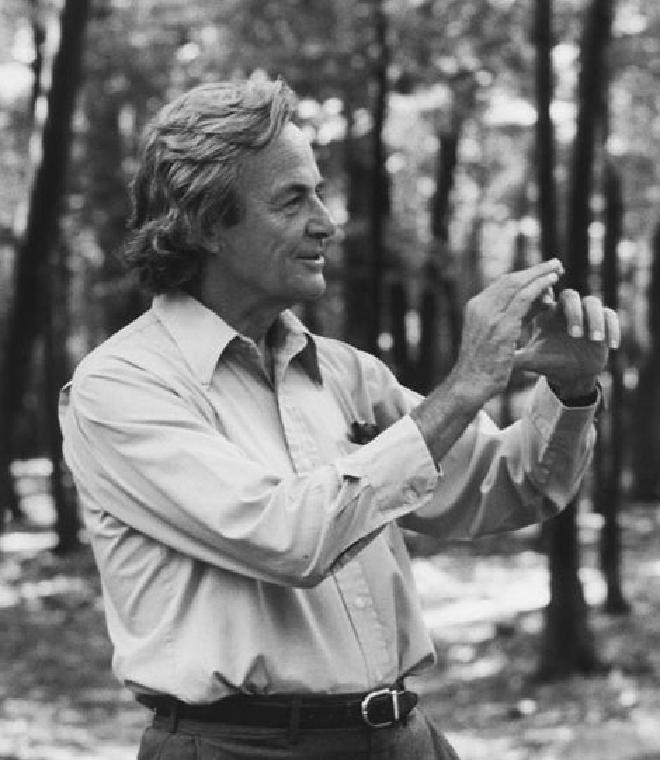

This part(and the rest of the article) is a summary(not complete) of the keynote talk given by Richard Feynman at a conference, where he introduces the difficulty of simulating physics in a near-perfect computer.

Feynman talks about perfect physics and turing-complete computers, and how to adapt physics to these computers. In particular, he tries to discretize physics to remove the troubles of handling infinities. He also sets the standard that good physics should explain new predictions while preserving the old theories’ predictions and features. He also shares that this new physics is going to be anisotropic, but asks, by how much?

Discretizing space and time means we have lattices for space and time jumps discontinuously. The next comparison is about the reversibility of natural laws and the assurance from computer scientists that the laws of computers are also reversible(which many thoughts were irreversible for a while). Here is an important formula to keep track of for the rest of the article.

Simulating Time #

Feynman goes further by pointing out that we first try to simulate classical physics and then turn to quantum physics. He starts by discussing how we simulate time, particularly, in cellular automata. CA are a great way to experiment with simulations before we jump into this serious business. We shall say, CA are playing grounds for simulation. Here, Feynman discusses time and space being initialized and not being simulated, hence, he comes up with some clever formalism that might help us simulate these aspects.

Simulating Probability #

He goes on to discuss the problems we face when we try to simulate probability, and this is where things got interesting. He splits two branches, he predicted the need for quantum computers to work with probability or the above formula might break down, the second being, tricking the computer to behave probabilistically. When trying to do the second branch, we encounter negative probabilities, as we encounter in Quantum Physics. We also encounter the issue of exponential growth of spacetime as we grow computer elements, which is not what we defined earlier. This is where he introduces tricking the computer to behave probabilistically and trying to get rid of the issue of exponential space growth. However, he goes further to demonstrate how the negative probability is an unsolvable issue with a classical computer using a thought experiment(which can also be done in real) making use of the double polarization of photons.

Discretization vs Quantization #

Perhaps, a common misunderstanding of the common public is that quantizing is the same as discretizing. Feynman answers this question brilliantly in the talk during the discussion. Discretization is the process of converting a continuous variable to a discrete behaviour. This is sort of pixelating the continuous variable. Quantizing a variable is the process of taking the variable from \( \mathbb{R}^4 \) or \( \mathbb{R}^3R \) to \( \mathscr{H} \), an infinite-dimensional Hilbert Space of operators whose eigenvalues might be continuous or discrete. More often, Quantum Mechanics’ Energy operators have discrete eigenvalue spectra, which makes many misunderstand the difference of the abovementioned processes. An example where the operators have continuous eigenvalues is the position and momentum operators. Their eigenvalues are continuous. This clarity, in Feynman’s words, will make our understanding clear and help us proceed further with our analysis and research.

What Happened After #

For simulating physics, most theoretical and computational physicists use computers to simulate/solve the equations to study the behaviour of dynamical variables of the system. The new idea that Feynman brought out was worked upon by Feynman himself, and that led to the birth of quantum computers.

A Doubtful Analogy #

Remember Boltzmann? Remember his contemporaries? All were hell-bent to make mechanical models of whatever it is they wished to study. Maxwell, went a long way supporting the Vortex Theory which claimed Electrodynamics can be explained by mechanical means. This set the development of physics to a halt for a long time(probably two decades?). They all loved making toy mechanical models, and Boltzmann was able to make complicated mechanical models that his contemporaries cannot understand how it works.

My doubt here is that, What if we are making the same mistake of trying to simulate physics in a computer? It might be possible that the attachment for a mechanical model might be at a gross level and the act of simulating in a computer lies in a subtle level. More musings on this in a future article!

References #

Feynman, R.P. Simulating physics with computers. Int J Theor Phys 21, 467–488 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02650179