Is Emergence Fundamental?

Many physicists today drive their research based on the fact that emergence is fundamental. For example, the Ehrenfest theorem shows that Quantum Mechanics has a classical limit where we can get the results of Classical Mechanics.

Or take Lorentz transformations and Galilean transformations of spacetime. Galilean transformations of frames of reference emerge from Lorentz transformations as a special limit of the speed of light \(c \rightarrow \infty \). We say that Galilean transformations are a subset of Lorentz transformations or Lorentz transformations are a more fundamental law of transformation.

This is called the emergence of a relative theory from a more fundamental theory. But why should the phenomena of emergence be fundamental? Why hunt for more fundamental principles if we can’t test the present theories at hand?

The answer to the latter is that finding a more fundamental theory - that is already restrained by experimental data and theoretical constraints - that is internally consistent leaves us with a handful of choices to pursue. We know that the internal consistency of a theory is a necessary condition for it to hold true but is not sufficient.

Answering the prior question is a tricky business. To discuss emergence, we have to discuss causation. George F. R Ellis explains three variants of causation in the below episode of Closer to Truth.

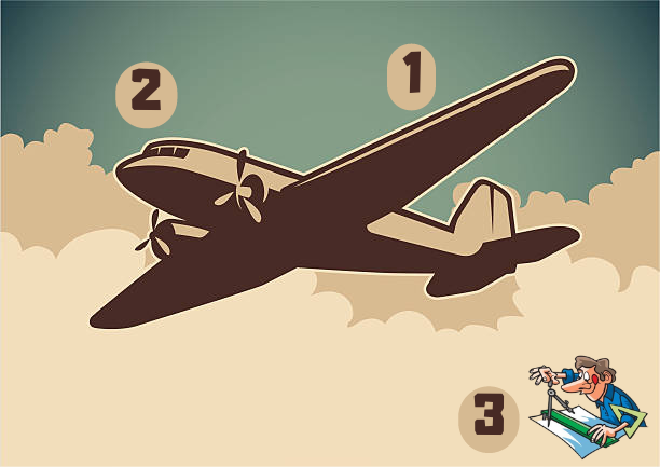

He uses an analogy to explain the three varieties of causation and shows how all three work together. He uses the example of a jumbo jet.

Bottoms-Up causation(1) is the pressure difference generated around the wings of the flight that pushes up the aircraft to fly in the air.

Top-Down causation(3) is the engineer using his brain to design the aircraft to fly. This is the causation that sets limits or boundary conditions on the bottoms-up phenomena.

Middlegrounds causation(2) is the pilot driving the flight.

We know from experience that all three are necessary for the aircraft to function as intended.

These three causation are decoupled in different branches of knowledge. Science bothers only with (1), Theology bothers the most with (3) and pragmatists bother the most with (2). So, no single field has a say over the other if they don’t discuss the other causation in any action or event under study.

How does all this discussion on causality help us understand the fundamentality of emergence? One way to look at it is when we see the fundamental theory being the cause of the emergent theory. Another way to look at it is that all the scientific laws are compendious connotations of a sequence of various experiences. This means all laws, fundamental or emergent are simply an abstraction of this sequence of various experiences. The better the sequence, the better the fundamental law is.

So, the latter view supposes us that it is the nature of the collection of sequences that gives rise to the abstraction of the scientific or philosophical laws and should inherently depend on the phenomena of emergence. This means we can say emergence is fundamental as long as we don’t change the way we do and practice science.