Unspoken Section of Quantum Mechanics

Every Pop-Science book on the market speaks about Quantum Entanglement, Quantum Information, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, Bohr’s atomic model, Measurement Problem, Schrodinger’s Cats and a lot more. Almost all of the above-mentioned topics are a consequence of two aspects of Quantum Theory. One is the Hamiltonian that describes the system, and two is the Evolution Equation(Schrodinger’s or Heisenberg’s) that determines the changes in the system with progress in time. The Evolution equations and their inputs have been constructed based on observations and theoretical decisions made by the brightest physicists of the time. However, the actual ingredient of the Quantum Mechanical Theory is the Hamiltonian of the system.

The syntactic picture of a theory identifies it with a body of theorems, stated in one particular language chosen for the expression of that theory. This should be contrasted with the alternative of presenting a theory in the first instance by identifying a class of structures as its models. In this second, semantic, approach the language used to express the theory is neither basic nor unique; the same class of structures could well be described in radically different ways, each with its own limitations. The models occupy centre stage. – Van Fraassen (1980, p.44)

Here, the syntactic picture of a theory is the axiomatic description of a theory and the semantic approach is the pragmatic section of the said theory, e.g, a family of differential equations. Schrodinger Equations come under the semantic approach. The formalised picture or the syntactic picture is more vivid and a little out of the scope of this article, but shall be discussed in future articles.

One may know all of this and not know any quantum mechanics. In a good undergraduate text, these . . . principles are covered in one short chapter. It is true that the Schrodinger equation tells how a quantum system evolves subject to the Hamiltonian; but to do quantum mechanics, one has to know how to pick the Hamiltonian. The principles that tell us how to do so are the real bridge principles of quantum mechanics. – Cartwright(1983, pp. 135-136)

It is a skill to frame a hamiltonian for the system that represents the actual physical system in the real world. This framed system is called a model of the physical system. Physicists deal with models all the time. Whether the model itself represents an actual physical system or just a pragmatic tool for the prediction of quantities of the physical system is metaphysical and is worth discussing in future articles. However, a model means something, but what is it anyway?

There are two ways we can think of the models we use in physics, and both are interrelated. Firstly first, a model is a mathematical structure containing sets of elements on which certain operations and relations are defined. Secondly, second, a model is a Tinkertoy construction of an Eiffel Tower(example from Structure and Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, R.I.G Hughes, p.80-81). A Tinkertoy represents Eiffel Tower but it is not an Eiffel Tower. When we mean a Tinkertoy represents, we mean it preserves some features of the original Eiffel Tower, like size ratios, the shape of the curve etc. Just like 2 similar triangles in geometry, but is a much broader sense. Similarly, a point in the mathematical structure of the model can represent the physical characteristic of the system we are studying using the said model.

There is the preservation of relations and points in the Tinkertoy model of the Eiffel Tower that is also present in the actual Eiffel Tower. In a similar sense, the relations and points of the mathematical structure of Hilbert Spaces of Quantum Mechanics are related to the actual physical system we are interested in. Cartwright explains this skill of constructing Hamiltonians as, “to hook up phenomena with intellectual constructions”.

The usual method to construct Hamiltonian of a system is to construct Lagrangian \(L\) or Lagrangian Density \(\mathcal{L}\), apply a Legendre Transform on the constructed Lagrangian \(L\) or \(\mathcal{L}\) to obtain the Hamiltonian of the system. We are but one step further to the construction of Hamiltonian, now we are stuck with the construction of Lagrangian. This is merely a translation/rephrasing of the original problem rather than the solution. However, we know that a Lagrangian for the system is defined as: $$ L=\sum T-\sum V $$ Here, \(T\) is the Kinetic Energy and we add all of them present in the system and \(V\) is the potential energy and we add all of the potential energy present in the system. Then we subtract them to obtain the Lagrangian of the system(or density if we provide density variants of Potential and Kinetic Energies). Now, the story doesn’t end there, constructing Lagrangian in a form that represents the symmetries of the system leads to insights into the system without actually solving for the dynamical equations of the system. In writing out the Kinetic and Potential energies, we get to choose our dynamical variables that represent the states of the system. It can be position & momentum, it can be a Wilson Loop(something I studied sparsely), it can be geometry etc. There are a lot of choices and constraints in choosing a particular way to represent a system in our mathematical model, but the art of constructing such models lies with the researchers in their own fields. Lattice Gauge Theorists would have guidelines to construct Lagrangians that are pragmatic for their calculations, String Theorists would have their guidelines to construct one, Loop Quantum Gravity people have their own guidelines etc. There is no set-in-stone procedure for constructing Lagrangians.

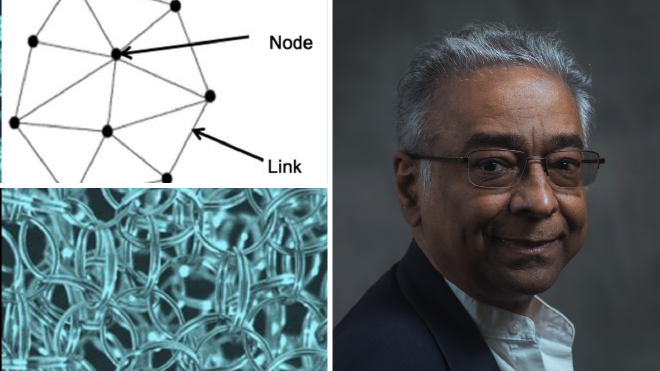

This freedom to construct Lagrangians opens space for creativity in Physics, although the previous theories and experimental data impose tremendous amounts of constraints on the limits of creativity, there is still room for some. For example, Einstein Prize winner, Abhay Ashtekar, quantized Gravity and formulated Loop Quantum Gravity. The usual recipe for quantisation of a field theory is to write the Lagrangian of the system, elevate the status of the dynamical variables of the system to operators in Hilbert space(if variables are continuous) and determine the commutation relations of the said operators. The initial attempts to quantise gravity involved Lagrangians written for Einsteinian General Relativity as a function of metric, the quantity that defines the shape and distances in our curved spacetime(a quantity to be used to construct the curved spacetime, can be likened to a generator function of spacetime). However, Abhay Ashtekar used Christoffel symbols(affine connection/parallel transport if you aren’t a mathematician - it is a quantity in Differential Geometry that helps us transport a vector from one point to another by providing the recipe for converting bases of the origin point’s vector space to the destination point’s vector space since each point has its own space and basis in curved spacetime) as dynamical variables and elevated it to operators and defined loops as the fundamental characteristic of spacetime(hence the name Loop Quantum Gravity).

This part of physics, where we smash our heads to construct a Hamiltonian to describe a said system, is quite unspoken of, not just quantum physics but all the physics, outside and inside the physics community. Those who do, know, those who don’t, don’t. These are not openly discussed in Undergrad Physics courses, a select few notice such peculiarities, and a subset of that only thinks about it. Just like the history and the gravity of the Least Action Principle are not discussed, but shown a waving hand just like Captain Jack Sparrow claims(but doesn’t do so), there are a lot of crucial points that go unnoticed or are kept for Graduate Physics. In that scenario, how will the common public know about that, if not communicated by the serious practitioner? What will they do, if they know these? And what will the passerby undergrads do if this is brought to their attention and are forced to think about it?